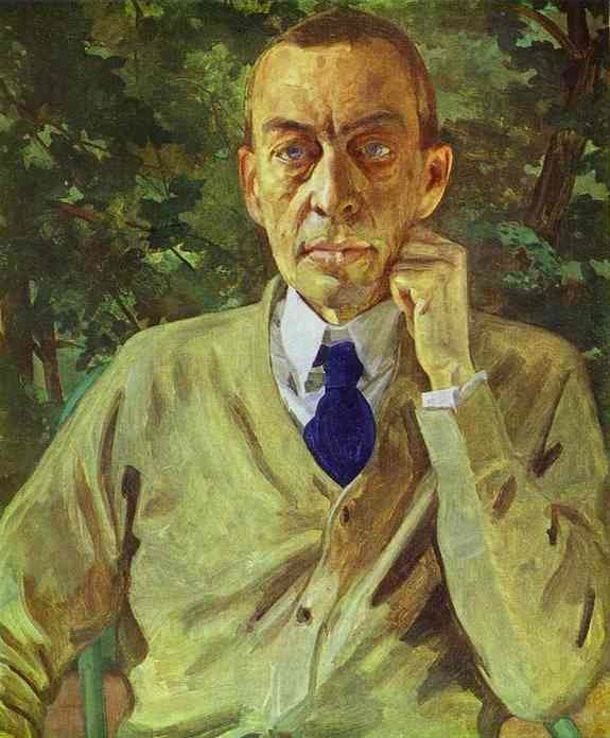

Sergei and Me, A Relationship in Four Works: 3, the Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor

Dispatches from the Forgotten Stars, #17

It’s taken me longer to get back to this project due to some unforeseen life stuff, but here we are…and it hasn’t just been the life stuff that’s given me pause on this installment. It’s been how to approach the subject in the first place. Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto is almost certainly the most famous of all four of his concertos; the first is a powerful if youthful work, and though the fourth has its champions, it has never achieved the beloved status of the middle two. Only the third, with the staggering virtuosity it demands of its soloist, rivals the second for sheer popularity.

But for all that, and for all the times I’ve heard it over the years, I kept trying to figure out a way to frame my writing about it here.

Then baseball came to the rescue.

Baseball? What does baseball have to do with Rachmaninoff and his Second Concerto, which was composed two years before the very first World Series? Well, nothing…but for a particular parallel between Rachmaninoff and a pitcher from the Atlanta Braves.

As a Pittsburgh Pirates fan, I quickly learned to hate the Braves in the early 90s, as they got good seemingly out of nowhere, going from last place in the NL West in 1990 to first place in 1991 and then repeating in 1992. Both years, the Braves defeated my Pirates in the National League Championship Series (the Pirates had also lost the 1990 NLCS to the Reds), on the strength of a pitching staff that was just starting to coalesce into one of baseball’s best starting rotations ever. But in 1991, when the Braves were flirting with contention, one of their pitchers was a guy named John Smoltz. Smoltz was, at the time, not very good. His career numbers to that point were middling, and his 1991 season started badly: he was something like 3-11 at one point, with an ERA over 5.00. (If you don’t know, trust me: those aren’t good numbers.)

So there I was, as a Pirates fan, not being terribly worried about the Braves because their rotation was two guys, a disaster named Smoltz, and a couple other guys. Big whoop.

Only…sometime in the middle of that season, Smoltz went to see a sports psychologist, and whatever happened in those sessions worked wonders, because John Smoltz became unhittable. Seriously, from mid-1991 on, John Smoltz pitched long enough and well enough to secure a spot in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

This is what brings us to Rachmaninoff.

After the premiere of his First Symphony, Rachmaninoff might have been classical music’s answer to John Smoltz: a talented guy who was on the ropes, career-wise, because that very premiere was an absolute disaster. Rachmaninoff’s score was likely beyond the technical abilities of the orchestra that played it, and the conductor, Alexander Glazunov (himself one of Russia’s finer composers whose music is still heard today), may well have been drunk at the concert. The resulting performance was so bad that composer-critic Cesar Cui wrote one of the enduring negative reviews in all of classical music history. Here’s the money quote:

If there were a conservatoire in Hell, if one of its talented students were instructed to write a programme symphony on "The Seven Plagues of Egypt", and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr Rachmaninoff's, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and delighted the inmates of Hell.

Ouch. Seriously, ouch.

The premiere of his Symphony No. 1 was such a fiasco for Rachmaninoff that it drove him into a deep depression, during which his only musical work was limited to performance only; he couldn’t compose to save his life. Rachmaninoff’s mental health seems to have been a concern his entire life, but in this particular instance, he was driving into a debilitating depression that completely sapped his productivity. He tried several approaches to curing himself, including visits with author Leo Tolstoy, to no avail; finally he ended up visiting a physician named Nikolai Dahl, who devised a treatment involving hypnosis and supportive therapy (actual psychotherapy, a la Freud, hadn’t come along yet). The hypnotic treatments apparently involved, in part, Dr. Dahl repeating a mantra to the composer: “You will write your concerto, and it will be of great quality. You will write your concerto. It will be good.”

And though it took Rachmaninoff nine months, he got the Second Piano Concerto written. This time the premiere was a smashing success, with Rachmaninoff himself playing the piano. The Second Concerto has endured in the concert repertoire ever since, and it is likely the most beloved Russian piano concerto of all time, save possibly Tchaikovsky’s First.

Rachmaninoff opens not with fireworks, either orchestral or pianistic, but with a series of chords by the soloist: minor chords, punctuated by pedal tones, that progress along until a rhythm takes over the orchestra enters with the first melody as the piano swirls alongside with a series of arpeggios. The feeling is one of agitated anxiety, dark and moody, and this mood will recur throughout the movement, including a middle section that sounds as purely Russian, in that great fiery way, as any music I’ve ever heard. Interpolated throughout is a second, more lyrical theme, but the mood shifts back and forth, to and fro, until the movement ends with decisive aplomb.

The second movement, though, gives us archetypal slow-movement Rachmaninoff. A delicate intro leads to a gorgeous melody as the piano again accompanies, first heard in the clarinet. If this melody sounds familiar, that’s because it probably is: singer-songwriter Eric Carmen, would borrow that melody for the tune of his hit ballad “All By Myself”, seventy-plus years later. (More on this on my official site!)

In the last movement, we have the most extroverted portion of the whole concerto, when the soloist is put on full virtuosic display, with a structure that serves Rachmaninoff very well: a dazzling opening that leads to a theme of almost martial character, that contrasts with a lyrical midsection that yields to a stormy development and a final climax that finally dispenses the clouds and brings things to a close on a triumphant note.

The entire concerto only lasts about half an hour. I don’t know if Rachmaninoff’s state of mind and the lingering unpleasantness of his First Symphony’s reception had anything to do with that; perhaps he still felt a need to not outstay his welcome. In the wake of the Second Concerto’s success, he would be more comfortable stretching his works; his Second Symphony, to which we will return, is a well-and-truly epic journey all on its own. The Second Concerto’s proportions all work in the piece’s favor, as it certainly leaves the audience wanting more. The work’s enduring popularity has extended beyond the concert hall, as its melodies are mined for song, certain passages have been reworked into program music for figure skaters, and the concerto was even used as a model for a well-known piece of film music, the “Warsaw Concerto” by Richard Addinsell, composed for the film Dangerous Moonlight.

And all of this is owed to a certain Russian doctor who came to the aid of an emotionally damaged composer whose career might have ended before it truly began, had Dr. Dahl not been able to make Rachmaninoff believe that he still had good music within him that was still waiting to be heard. Poet Diane Ackerman wrote a poem about this whole episode that’s a favorite of mine; her poem ends thusly:

Listening to Rachmaninoff’s

concerto today, intoxicated by its fever,

I want to kiss the hands of Dahl,

but he is beyond my touch or game.

Allow me to thank you in his name.

Indeed.

Here is Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2, played by the amazing Khatia Buniatashvili. Ms. Buniatashvili is one of my favorite pianists because not only does she play wonderfully and expressively, but watching her conveys a constant sense of joy and delight in the very act of music-making. Watch her when she’s not playing: she turns to the orchestra and listens with obvious love and involvement.

Next up: a post that I’ve been kicking around in my head for years, and I think it’s finally time to get it out. It’s Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony, which resides in a part of my heart where few other works manage to tread.

Exeunt,

-K.

That was the period I was ACTUALLY following baseball. And hating the Braves.